We asked children, young people and adults to tell us what good wellbeing means to them, to identify the things that get in the way, and tell us what we should do about it.

We are grateful to the more than 10,000 New Zealanders, including over 6,000 children and young people, who contributed to this report by sharing their thoughts, knowledge and expertise with us.

This report is a summary of what we heard during our engagement and brings together the key themes from a range of meetings, interviews, written submissions, postcards to the Prime Minister and responses to surveys. A combination of methods was used to analyse and summarise this information, but we have tried to use the words and voices of the people we spoke with as much as possible.

A message from the Prime Minister#

A huge thank you to everyone who took the opportunity to share their ideas, experience and perspectives about what will help achieve our Government's goal of making New Zealand the best place in the world for children and young people.

Around 10,000 people made time to send in a submission, share ideas at the numerous meetings and hui, complete the online survey or send me a postcard outlining how we could make things better for our kids - and that included children themselves.

Reading through the hundreds of 'Postcards to the Prime Minister' had a huge impact on me. I read every single one and was really impressed by how deeply young New Zealanders care about each other and about ensuring everyone has more opportunities for a better life.

The feedback summarised in this report, I believe, reflects a strong Kiwi sense of fairness and equality and a belief that everyone deserves decent opportunities. And that starts with children. Every child deserves to have the best start in life; now it's our chance to make that a reality together.

Rt Hon Jacinda Ardern

Prime Minister

Minister for Child Poverty Reduction

A message from the Minister for Children#

For the Child and Youth Wellbeing Strategy to be successful, it has to reflect what children and their families want. They are the people this strategy is for and it has to work for them. As a Government, we have aspirations about making peoples' lives - especially children's lives - better. So we simply had to listen to the children and their families.

That's why this public engagement process was so important and there is no question that what young people have told us has greatly helped our thinking. Reaching those whose voices are less often heard was a particular focus of the engagement and I'd like to acknowledge the support of the Office of the Children's Commissioner, Oranga Tamariki, Te Puni Kōkiri and the Ministry of Health in achieving this. The rich feedback outlined in this report builds on insights from previous research and engagement and is helping to shape the direction and content of the first Strategy, due to be published later this year.

Many of the issues we need to tackle are complex, stubborn and intergenerational, so we know change will take time. That's why the Strategy will be reviewed and updated regularly, to ensure it continues to meet the changing needs of New Zealand's children and young people.

While Government needs to lead this work by setting the future direction as well as the immediate actions it will take, it cannot bring about change by itself - collective action is needed. I encourage all New Zealanders to help ensure that we improve the wellbeing of our children and young people.

They deserve the best.

Hon Tracey Martin

Minister for Children

A snapshot of what we heard#

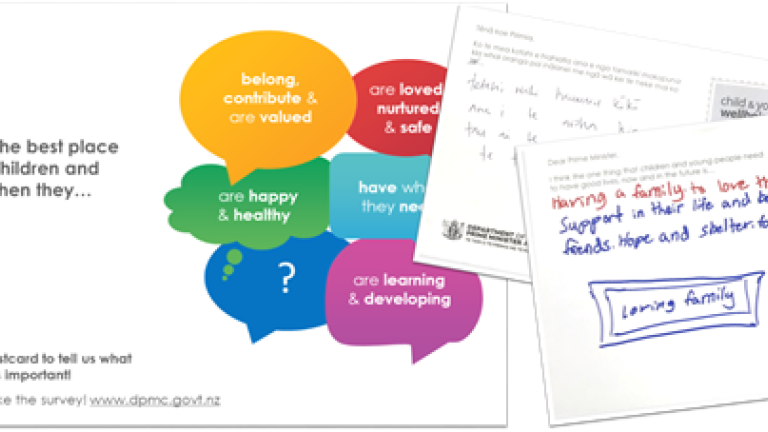

This report has been prepared by the Child Wellbeing Unit, Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet. The Child Wellbeing Unit was established to support the Prime Minister, in her role as the Minister for Child Poverty Reduction, and the Minister for Children in the development of New Zealand's first Child and Youth Wellbeing Strategy (the Strategy)

We asked children, young people and adults to tell us what good wellbeing means to them, to identify the things that get in the way, and tell us what we should do about it. We are grateful to the more than 10,000 New Zealanders, including over 6,000 children and young people, who contributed to this report by sharing their thoughts, knowledge and expertise with us. The Office of the Children's Commissioner and Oranga Tamaraki led the engagement with children and young people, and many of the views and voices of children and young people presented in this report have been drawn from their joint report What makes a good life? Children and young people's views on wellbeing1.

This report is a summary of what we heard during our engagement and brings together the key themes from a range of meetings, interviews, written submissions, postcards to the Prime Minister and responses to surveys. A combination of methods was used to analyse and summarise this information, but we have tried to use the words and voices of the people we spoke with as much as possible.

There were a number of key themes that emerged throughout the engagement. These themes have been summarised below.

Change is needed, and it's needed now#

The majority of children and young people are doing well, but some are facing significant challenges. Almost everyone who shared their views, including those who said that they were doing well, could point to something that needed to change if children and young people are to have a good life. People want to see some clear and immediate actions as a first step in a process of thorough ongoing, systemic change. They want government to take some actions to make this happen, but government alone can't achieve the vision for the Strategy. Every New Zealander has a role to play in making New Zealand the best place in the world for children and young people.

The Strategy needs to be bigger than the government of the day#

Adults told us they had high hopes that something real and tangible will come from the Strategy, but worried it may end up being discarded with any change in government. Adults told us that child wellbeing is too important to be a 'fad' and that this Strategy shouldn't be about short term solutions and ‘easy wins'. They emphasised the need for long-term commitment to actions that would lift the wellbeing of all children and young people and change some of the major systemic issues that have typically been considered “too hard” or “too big” to address.

Local communities are integral to the success of the Strategy#

Local communities have an important role to play in the Strategy. Children and young people told us about the importance of the different communities in their lives. Services must accept children and young people for who they are and respect their critical relationships with their family, whānau and communities. Adults told us that without the local level insights, involvement, and their support, any nationally driven strategy would fail. A one-size-fits-all strategy won't work. Adults told us that the Strategy needs to support locally-led solutions and to empower and enable communities to make changes themselves.

The Strategy needs to have a focus on family and whānau wellbeing#

Children, young people, and adults told us that families and whānau must be well in order for children to be well, and families must be involved in making things better. A major theme from adults and children alike was putting families and whānau at the centre of solutions - children, young people, and adults told us that parents, caregivers, family and whānau often need support too, and that children's wellbeing is impacted by their families' wellbeing. Many adults felt that there needs to be an explicit focus on families and whānau at all levels of the Strategy.

Te Tiriti o Waitangi should be a clear and empowering dimension of the Strategy#

Adults told us that the Treaty of Waitangi (Te Tiriti o Waitangi) should be a clear and empowering dimension of the Strategy. This includes getting serious about services and solutions for Māori being designed and delivered by Māori. People told us that recognising and giving practical commitment to Te Tiriti o Waitangi, and the objectives of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, is essential to achieving wellbeing for tamariki and rangatahi Māori. Institutional racism against Māori was often raised as a significant barrier to personal and intergenerational wellbeing.

The Strategy needs to focus on reducing inequity#

The issue of equity/inequity was also a strong theme across the engagement. Adults talked about equity in terms of outcomes, and children and young people talked about fairness. We heard a lot from children, young people and adults about the importance of ensuring all children had the basics. While most children and young people are doing well, many face major challenges. Poverty, material hardship, and the high cost of living were identified as significant barriers for many children and families and whānau. Some communities and families are living in entrenched poverty and really struggling. When asked where government should prioritise its focus, ensuring all children "have what they need" (e.g. housing, meeting material needs, addressing poverty etc.) received the strongest support from children, young people and adults alike.

A good life is more than the bare basics#

Children and young people told us they want to be accepted, valued and respected. They want to feel safe in their homes and communities. They want to be with people who care about them. The children and young people we spoke with recognised their need for basic things, but they were hopeful that their future would include more than that. A minimum standard of living is not enough. Adults also wanted more for children and young people than the absence of risk, deprivation or harm. They emphasised the importance of a positive framing of wellbeing, and told us that reducing poverty is an admirable and important goal, but that it shouldn't set the tone and aspirations for a wellbeing strategy.

Children and young people have a right to be included in the decision-making process#

There was a lot of advocacy by adults for the inclusion and consideration of children and young people's voice in the Strategy and in any decisions that impact on children more widely. “Being listened to” was mentioned by children and young people as one of the things that could help them have a good life. Many of the children and young people who contributed their ideas, stories and opinions were grateful for being asked, and for many it was the first time they had been asked or felt they were being heard.

Invest in ensuring all kids get a great education#

Children and young people spend a lot of time at school and the ones we spoke with told us how important their education is to future opportunities. Schools can have a major impact on children and young people's wellbeing, for better or for worse. Children, young people and adults all said we need to invest more in education to make it more accessible and a quality experience for everyone.

Focus on early intervention and specifically on the first 1,000 days#

There was significant support for placing a greater emphasis on providing support earlier. This meant providing services to children, and their families and whanau, at younger ages; providing services before things reached crisis point; and providing more services that took a preventative approach.

Government agencies and community services need to work together better#

Adults told us that government agencies are not collaborating, and services competing against each other for funding was identified as a major barrier. We were told some new initiatives will be needed but a lot could be achieved if government agencies and community services were able to communicate and collaborate more effectively. Children and young people talked about their lives as a whole. Their needs do not exist within neatly-defined categories. The development of the Strategy is an opportunity to respond to children's and young people's needs using holistic and comprehensive approaches to wellbeing.

Background#

A Child and Youth Wellbeing Strategy is required by legislation#

Amendments to the Children’s Act 2014 require successive governments to adopt a strategy to improve the wellbeing of all children and young people. There’ll be a particular focus on reducing child poverty and on those with greater needs, including children of interest or concern to Oranga Tamariki. The Government is required to develop and publish the first Child and Youth Wellbeing Strategy by 21 December 2019.

The Child and Youth Wellbeing Strategy will set the direction for government policy and action#

The Strategy will provide a framework to drive government policy and action on child wellbeing. It will commit Government to set and report on outcomes and actions to improve the wellbeing of all children and young people.

The Strategy will set out the Government's desired outcomes for our children and young people and make concrete commitments for change. It will also clearly outline how progress will be measured and reported on so that we can see the difference being made and where more work might be needed.

For the Strategy to work, it must be shaped by the interests and aspirations of children, young people and their families, and by those who work directly with them.

Reaching Māori and children and young people#

The new legislation requires consultation with representatives of Māori and with children and young people, as part of developing the Strategy.

The Office of the Children's Commissioner and Oranga Tamariki formed a project team that led most of the engagement with children and young people as an input into the Strategy. Over 6,000 children and young people shared their views on what wellbeing means to them; 423 through face-to-face engagement through the focus groups and interviews, and 5,607 children and young people through an online survey. These engagements have been summarised in their report, What makes a good life? Children and young people's views on wellbeing2. The report's key findings and some direct quotes have also been incorporated into this report. Where direct quotes have been used, we have indicated this with an asterisk, and page number.

Additionally, the Child Wellbeing Unit also engaged with children and young people as opportunities presented themselves during the engagement period. We heard directly from over 500 children and young people. More information about this is included in Appendix One. The key findings and some direct quotes from these children and young people have also been incorporated into this report.

Te Puni Kōkiri supported the engagement process by hosting a series of regional hui across New Zealand. Invitations to the hui were sent to a wide range of iwi and Māori organisations, including many non-government service providers operating in the children and youth sector and other social sectors. In addition, Te Puni Kōkiri utilised its local networks to extend invitations to relevant groups and individuals with an interest in this kaupapa. In total there were 11 regional hui with approximately 175 attendees. More information about these are provided in Appendix One and in the Māori Engagement Summary Report document.

Note, the hui were just one of the ways we engaged with Māori. In total, across all forms of engagements, over a quarter (at least 2,500) of the children, young people and adults who provided feedback identified as Māori.

A wide range of New Zealanders shared their views#

In addition to engagement with children and young people and with Māori, we also engaged with a range of other individuals, families and whānau, and population and sector groups. The design of the engagement, and lines of enquiry with children and young people, led by the What Makes a Good Life team, helped to inform the wider engagement with adults. We provided a range of different ways that other groups could ‘have their say', including:

- Ministry of Health workshops. The Child Wellbeing Unit attended ten workshops hosted by the Ministry of Health, in partnership with their local District Health Boards. There were approximately 700 participants across the ten workshops. More information about these are provided in Appendix One.

- Meetings, hui and other face-to-face engagements. In total we spoke with approximately 1,500 adults through the face-to-face engagements (including the Ministry of Health workshops and the Māori engagement hui). More information about these are provided in Appendix One and in the Māori Engagement Summary Report document.

- A survey for adults. The Survey was available online through the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet website and promoted by other Government agencies. A paper copy of the survey was also made available to a women’s prison and a men’s prison. In total 1,738 people provided feedback through the adult’s survey.

- A written submission process. This was open to anyone who wanted to provide written feedback, either as an individual or on behalf of their organisation. In total, we received submissions from 58 individuals and 153 groups or organisations

- A “Postcard to the Prime Minister”.The “Postcard to the Prime Minister” was a way for children, young people and adults to express their “big ideas” directly with the Prime Minister. Over 1,000 people sent the Prime Minister a postcard.

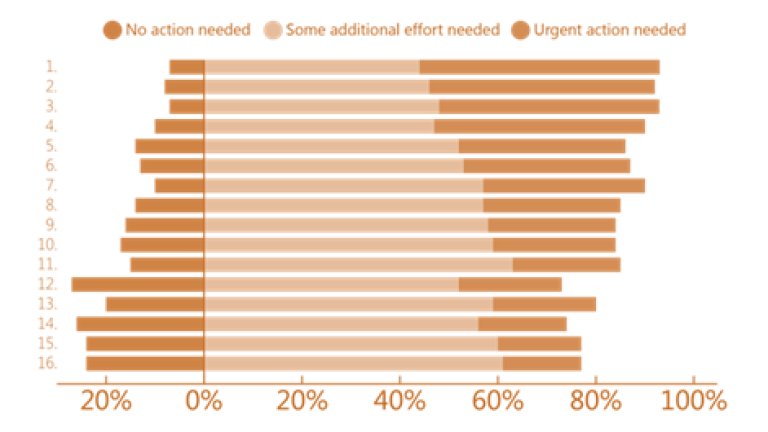

A proposed Outcomes Framework to guide discussion#

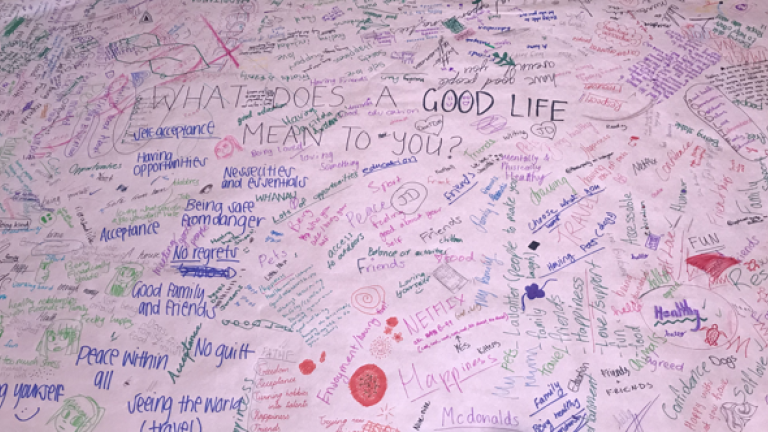

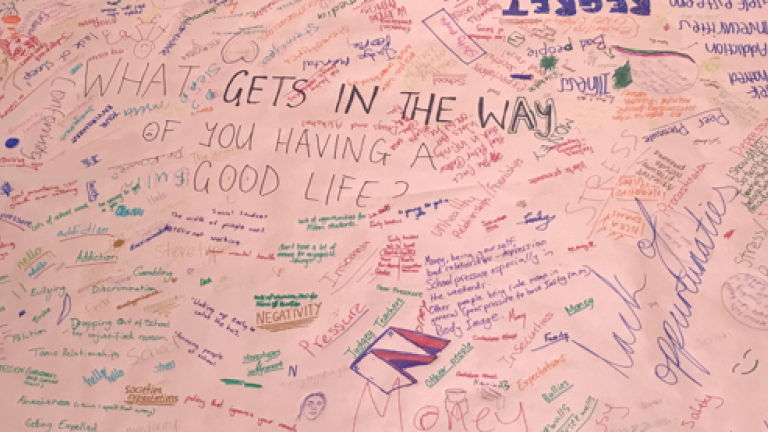

In September 2018, Cabinet approved a draft Outcomes Framework as the basis of the engagement process (see Appendix Two). It was made publically available and presented at (or provided in advance of) the face-to-face engagements. We asked for specific feedback on the proposed Outcomes Framework, including on the vision statement, principles, broad framing of child wellbeing, a set of outcome statements of what ‘good wellbeing' would look like, and an indicative list of 16 potential focus areas to inform the initial Strategy. We also had a set of open questions to prompt and guide discussion, including:

- What is good wellbeing in your own words? / What does ‘the good life' look like to you?

- What are the barriers or things that ‘get in the way'?

- What can we do to help children and young people have a good life?

- What is the one thing you want to tell the Prime Minister about what children need to have good lives, now and in the future?

Recording and analysing what people told us#

We used a range of different methods to collect and record feedback, in order to be responsive to the people we spoke with and the environments we were engaging in. At some of the face-to-face engagements, participants wrote notes and comments on cards which were collected and electronically transcribed for analysis. At others we had scribes taking notes on big pieces of paper (which participants could see) and these were transcribed for analysis. At some engagements we ended up just having a conversation and writing up notes afterwards. Wherever practical, we sent our transcripts of feedback to the participants for review.

Sometimes a single response represented many people (i.e. some submissions were written by a group of people, or organisations on behalf of their members), while individual people contributed varying levels - from single comments to pages of very specific and detailed feedback.

In total, we received around 600,000 words within submissions, notes, transcripts and responses to the survey in addition to the What makes a good life report. A mixed methods approach was used to analyse this information as accurately and systematically as possible. We identified common themes based on how often people talked about particular things (e.g. “food”, “family & whānau”, “safety” etc.) using a combination of computer automated text analysis techniques and manual coding techniques. We then took those themes and investigated them to provide more detail and context, and supplemented them with direct quotes that were reflective of comments people made. Finally, we asked people participating in the engagement process to peer review the analysis to ensure the main themes have been captured.

What makes a good life?#

In the survey and in face-to-face engagements, children and young people were asked an open-ended question about what having a good life means to them. Adults were asked to describe good wellbeing in their own words in the survey, and in many of the face-to-face engagements attendees were asked what they hoped for or wanted for the children and young people in their life. A broad range of topics were identified, including the key themes summarised below.

Being able to pursue your dreams and do what makes you happy#

Being happy and enjoying life was the most common theme identified in the children and young people's responses to the survey question about what having a good life means to them. These responsestalked about the good life as being able to spend their life enjoying what they are doing, having fun, and feeling happy. Children and young people want to play and participate in fun activities now, but they also want the things which would make them happy in the future, like a good job or opportunities to pursue their dreams.

Being able to wake up each day with a sense of happiness

Young person

Having a good life to me means that you should have somewhat of a happy attitude and that you should have your path in life decided by yourself and that you should go and follow it.

Young person (p.17*)

Happiness, fun and the freedom to be a kid was one the key themes identified in the adults' responses to the survey. About 15% of adults used the word happy or happiness to describe “good wellbeing” or what they hoped for the children and young people in their lives. They wanted the children in their lives to have opportunities to have fun, and just “be children”. However, some people cautioned against focusing too strongly on happiness.

…we have all sorts of emotions all the time, sometimes happy, but not always, and what matters is resilience, the ability to bounce back when life inevitably is difficult.

Adult

…I am working with a very anxious 11 year old girl at the moment, and her mum keeps saying to me “I just want my happy little girl back”. This is making things so much worse for the girl because she feels like her worried feelings are wrong and she is unloved unless she's feeling happy. The pressure to always be “happy” is doing damage to our young people.

Adult

The children and young people in the face-to-face engagements (those likely to have faced, or be facing challenges in their lives) talked about their hopes and dreams for the future. Some spoke about the importance of being hopeful and aspirational. Some mentioned looking forward to the future and being able to be more independent. Others mentioned specific things they were looking forward to in their future, such as getting married, having a job or having kids.

I think that an important step to having a good life is to do things that you like, with people that you like and that you take time to care about people and to feel cared for. I enjoy making decisions, taking responsibility and doing jobs because it makes me feel good because I have helped someone and that I have independence.

Young person

Having a loving family and good friends#

Having supportive family and friends was the second most common theme identified in the children and young people's responses to the survey question about what a good life means to them. In the face-to-face conversations, children and young people also talked a lot about the important role family and friends play in having a good life. Children and young people's relationships with their family and whānau are usually the most important, while the importance of friendships was emphasised more by young people than children.

Being with your family, even if they are annoying the heck out of you. They are immediate speed dial no.1.

Young person (pg.4*)

Being surrounded by positivity and supportive family and friends.

Young person

Children and young people wanted to be able to spend more time with their family and whānau. This included children and young people in the care of Oranga Tamariki. Children told us about how they want to be able to cook and have kai with their whānau, play with their cousins, see their grandparents and just be with their families and whānau.

Spend more time with family and if they are poor they still get to do all the cool and fun activities that we get to do.

Child

One in five adults used the word love3 to describe “good wellbeing”, and about 18% of adults used words relating to family and whānau4. Many people thought it was important for children to feel love and acceptance with a range of people, as well as learning how to love themselves and other people. Some people went further to emphasise the importance of unconditional and constant love. People also commented on the difference between ‘being loved' and ‘feeling loved' and the importance of having both. Adults talked also about the importance of children and young people having good role models and ‘good friends'. One young mum had specific hopes that her daughter would have a small number of really close friends. She talked about how important it was to have strong relationships with people who will accept and forgive you.

Someone that loves them and thinks they are important, doesn't need to be a parent but all kids need a special someone around that makes them feel loved

Adult

A child that is surrounded by love, in their family, friends and community. A child that can build resilience and has access to, and feel confident gaining, tools that can help them in life. A child that is confident and has knowledge to make informed decisions. A child that doesn't have race barriers because of society's expectations.

Adult

The material things#

Ensuring children and young people have their basic material needs met to a reasonable standard was the third most common theme raised by children and young people in the children's survey question “What does having a good life mean to you?' It was also in the top five themes from the adult's survey. Responses often mentioned having a warm safe place to sleep, enough (healthy) food for a full belly, and enough money for other things, like clothes and school trips.

Being able to afford the basics and sometimes the luxury things.

Young person

We were told that it's important that children, young people and their families not only have what they need today, but also have the security of knowing they will always be able to provide their children with at least the basics, and not have to live day-to-day.

A warm home, food on the table, adequate clothing, access to opportunity and the financial means to live without fear of being hungry, cold, and tired.

Adult

Being physically, mentally and spiritually healthy#

“Healthy” was the most common response from adults when asked to describe good wellbeing in their own words. One out of every four adults talked about health. Adults described health as a balance of mental, physical and spiritual health. Te Whare Tapa Whā, the model of Māori health developed by Mason Durie,was commonly referenced as a good model for thinking about wellbeing.

To wake up in the morning and be excited that it is another day. To have all my needs met - mental, physical and spiritual. To be loved and to love.

Adult

Te Whare Tapa Whā is a good representation of holistic wellbeing, so as long as relationships (whānau), physical health (tinana), mental/emotional health (hinengaro) and spiritual (wairua) are being attending to from the individual level to the political/wider social context, then it should cover it.

Adult

Physical and mental health also featured strongly in responses from children and young people about what having a good life means. They highlighted that health is a combination of both physical and mental health. Mental health was a stronger focus for young people (rather than children) who wrote about the need for accessible and affordable mental health treatment options.

A good life also means living mentally and physically healthy, or if not, having access to medical help (that you can afford).

Young person (pg.18*)

Feeling safe#

Safe (or Safety) was the second most common word that adults used when asked to describe good wellbeing in their own words. Adults talked a lot about children and young people needing safe environments- safe homes, safe schools, and safe communities. Safe was often used in the context of protection from harm, victimisation and bullying or abuse. However a very small number of adults cautioned against kids being “too safe”.

Safe. Being able to play outside with other kids or on their own and parents not having to worry about their safety.

Adult

They need to be challenged and put outside their comfort zone. Being safe and nurtured can be the opposite of this.

Adult

In their responses about what a good life means, children and young people also highlighted the importance of feeling safe at home, at school and out in public. Safety meant not only physical safety but also feeling safe to express their individuality without fear of judgement, rejection or harassment. Children and young people's sense of safety was affected by their own unique circumstances. For example young people who identified as part of the LGBTQI+ community also spoke about the need for safe spaces where they could explore their identity. Another young person with a physical disability said that stairs without railings are what makes him feel unsafe. Younger children were more likely than older children to mention their safety, particularly in regards to bullying.

Feeling safe in their company and being able to fully open up around them, without being scared of them judging you.

Young person (pg.35*)

Feeling accepted, valued and respected#

Feeling accepted was one of the strongest themes that came through the face-to-face engagements. It was mentioned by almost all children and young people. They mentioned acceptance in relation to culture, ethnicity, sexuality, gender, disability, mental health and being in state care. Feeling valued and respected was one of the key themes identified in responses to the ‘what does having a good life mean to you?’ question in the survey from children and young people. They mentioned religion, culture, belonging and acceptance as important aspects of this. Children and young people with a disability, as well as those who indicated their gender was other than male or female, were more likely to say that identity and belonging were important for a good life. Acceptance was mentioned by almost all of the children and young people in the face-to-face engagements. Children and young people wanted to be accepted by their family, their friends and their communities.

Teach acceptance more... Just so that people can learn to accept other cultures, because I feel like what's happened in the past is that people have been taught it's okay to just think within your one culture, and that's it for your whole life. But then the thing is the world is such a vast place.

Young person (pg.26*)

Children and young people talked about how they want to be accepted for who they are, supported in their identity, respected, listened to and believed in. They want choices and freedom. They want the important adults in their lives to help them build their confidence, self-esteem and self-worth, so they can realise their hopes and dreams.

To me a good life means that I can talk anytime I need the help. I want to be able to feel safe and confident with who I am… I want to be able to help people and ensure that everybody knows how amazing and loved they are. All I want is for others, and me, to be happy. You are beautiful. You are loved.

Young person

‘Valuing and listening to children' and ‘Acceptance and belonging' were also key themes identified in the responses to the adult's survey. “Valued” was one of the top five words that adults used to describe what good wellbeing means to them, but they were less likely to talk about children being “respected”. Less than 5% of responses talked about respect, and many of these did so in reference to children learning to respect others.

That children are responsible, respectful, resourceful, and trust that adults will guide them responsibly.

Adult

Knowing who they are, in regards to their cultural identity and language development. Being able to connect with people like them, so as to bond with each other, to prevent social isolation and stigma for being 'different'. Being accepted for their diversity and not to be bullied or demeaned. All diversity normalised.

Adult

Learning and education#

“Learning”, “growing”, “educated”, and “developing” were all common words that adults used to describe good wellbeing. When asked what they wanted or hoped for the children in their life, some adults talked about a good education so that they would be able to get a good job and have financial security later in life. Education came through as a strong theme, particularly for Pacific families.

I always talk to my children about how I want a better life for them - I'm a labourer and its good work, but I want them to get a better job than me and to do better in life than I did.

Adult

Children and young people highlighted the importance of feeling like they belong at school, and having teachers who are kind and care about them. They also talked about the importance of learning and education for future wellbeing. They saw this as an important part of helping them to become an adult and get a job. Young people were more likely to mention the importance of employment than younger children. The majority of children and young people spoke enthusiastically about learning. Even children and young people who spoke of past negative experiences with the education system, still expressed a desire to learn.

The most important things for children and young people to have a good life#

Children and young people were also asked to choose the top six most important things for children and young people to have a good life (from two lists of seven items). The items are presented below - from most commonly identified as important, to least commonly identified as important:

List 1

65% - Children and young people have good relationships with family and friends

57% - Children and young people are valued and respected for who they are

51% - Children and young people with health conditions are supported to live good lives

46% - Children and young people enjoy school and build skills and knowledge for life

43% - Young people have job opportunities when they leave school

37% - The environment is looked after

21% - Children and young people know their family's history (whakapapa) and their culture

List 2

71% - Parents/caregivers have enough money for basic stuff like food, clothes and a good house to live in

59% - Children and young people are kept safe from bullying, violence or accidents

47% - Children and young people have family, whānau, and people in their community and school they can trust and rely on

44% - Babies get a good start to life, so they grow up happy and healthy

42% - Parents have time to spend with and help their children

30% - Children and young people are able to share their views on important issues

26% - Children and young people have opportunities to do fun activities in their spare time

The things that get in the way#

The majority of children and young people that we heard from are doing well. However, the face-to-face engagements with children were aimed at ensuring we heard from the children and young people who were most likely to be experiencing challenges. Their experiences of these challenges have been incorporated in the summary below. We also asked adults to talk about barriers or “the things that get in the way of children's wellbeing” through the survey, face-to-face engagements and through the written submission process. We received a lot of feedback from adults experiencing significant hardship or working with people experiencing significant hardship.

The most common themes that were raised are summarised below. This is not an extensive list of all the barriers identified by children, adults, and young people.

Poverty, financial hardship and the cost of living#

'Poverty, financial hardship and the high cost of living' was the most common theme that adults identified as a barrier to wellbeing. Over 40% of adults talked about food insecurity, lack of good quality housing, poverty, lack of money, and/or the cost of things as key barriers to wellbeing. Raising benefit levels, reducing the cost of things, or ensuring access to good employment were seen by many as the solution that would have the biggest impact on child wellbeing.

…We could solve all these problems if parents were just able to get a good job with good pay. Not having enough money causes all the problems and then makes them all worse. A real minimum-wage where parents could have enough money from one job would make all the difference. My husband has to work two jobs when I am pregnant or with the children and I feel bad because two jobs is too much for one person, but it's still not enough money.

Adult

The children, young people and adults in financial hardship talked about their experiences. Adults told us that they are in “survival mode”, while one young person described it as “living hard”. They told us about not having enough money for food, bills and petrol, about not being able to afford healthcare, and about living in overcrowded housing. Girls spoke about ‘period poverty' (a lack of access to sanitary products because of cost). Some young people told us about their experiences of being homeless, or how not having enough money can lead them to committing crimes. Many talked about being stuck in a cycle that won't get better.

Money may not be the key to happiness but it is the key to living and I know many people who struggle.

Young person (pg.31*)

Sometimes you can't afford what you need. Can't afford experiences - camps and school trips, education, food - like if you have bad health because you can only afford the bad stuff, you're never gonna get healthy.

Young person (pg.31*)

Children and young people told us about their parents being in insecure work, which can mean going from work to the benefit (and having times with no money in between). They also talked about missing out on opportunities because they didn't have the money to pay for them. They talked about their parents being stressed about money a lot and being embarrassed when they can't pay for stuff.

Not being able to afford things - like sports or activities. People try to help us to make it easier but it's shameful.

Child (pg.31*)

I have to save all year for Christmas, it isn't something you can do a month in advance, it takes all year. You can't go to WINZ and ask for money for a birthday but the kids expect and want birthday presents and to have their friends over and so you need to save for that.

Adult

Young people with disabilities sometimes spoke about their families not having enough money because of their disability. They spoke about how families can't always cover the costs of the extra supports that they might need to have a good life. As a result, the family may not be able to afford things that they otherwise would. Children and young people wanted to spend more time with their whānau. Some said their parents have to work two jobs and don't have any time for anything else.

Abuse, neglect and harmful family environments#

People told us that families and whānau are a major influence on children and young people's wellbeing, but not always in a positive way. Whānau were sometimes a barrier to having a good life when, for example, they were not accepting of the child or young person's identity, or when whānau were the source of violence and drugs. ‘Abuse, neglect and harmful family environments' was the second most common barrier identified in the adult survey responses. About a third of adults talked about family and whānau being a barrier to good wellbeing. People talked about parents' mental health issues, drug and alcohol addictions, selfishness, divorce, and family violence as adverse childhood experiences and hugely detrimental to children and young people's wellbeing. Children and young people talked about the physical and emotional trauma caused by past events, such as the pain of being separated from their parents, living in a ‘broken home', or experiencing violence in their home.

When I go home I'm getting ready to battle the devil.

Young person (pg.35*)

Many adults recognised that parents' lack of skills or time to support their child's wellbeing was often due to their own childhood experiences of poor parenting, lack of role models, or the other stressors in their life. There was a strong emphasis on providing more support for parents and disrupting intergenerational cycles of abuse and poverty. A number of adults talked about how we need to stop assuming that good parenting comes naturally, and incorporate child development and parenting skills into the curriculum at an early age.

Children and young people talked about how they wanted parents to be able to be the best parents they could be and how sometimes that meant needing services like counselling or addiction support, or support to make better choices.

1). Parents who themselves have not had the opportunity to develop their own potential and feel inadequate for whatever reason. 2). Low wages of some jobs and consequently parents being preoccupied and stressed by the family's lack of resources (money, accommodation, skills).

Adult

A better environment for our whānau and parents creates a positive and better environment for our children.

Young person (pg.39*)

We heard from parents who had been separated from their children, who spoke of the pain and heartache of having their children taken away, and the fear of being reunited without getting the support they need. Children and young people (particularly those in contact with Oranga Tamariki) wanted to live with their whānau and not be separated from them, but they also emphasised the importance of support for their parents. They recognised that their whānau unit needed to be well in order for the children to be well. Some wanted their whānau to be better supported by their community and by professional support services. Without this support, their parents might not be able to take care of them anymore, which would impact on them.

Drugs, alcohol and addiction#

For some of the children and young people we spoke to, drug and alcohol abuse is a normal part of life in both their family and their community. Children and young people told us how drugs can play good and bad roles in their life. Most acknowledged that alcohol abuse can have negative impacts on them, their family and their friends.

However, for some young people, alcohol and drugs can also be a way to cope with life or escape from reality and have a good time. One young person spoke of how he regularly had to look after his younger siblings. He found this stressful, so would smoke pot to help him be more patient. Young people talked about the pressure to fit in, which could mean drinking, smoking, doing drugs or self-harming.

The drugs help me deal with depressions, helps me forget about it, escape, get away.

Young person (pg.36*)

About one in seven responses to the adult survey talked about drugs, alcohol, or addiction as a barrier to children and young people's wellbeing. It was also discussed at many of the face-to-face engagements and in about 15% of written submissions. Adults regularly commented on the harm that alcohol, drugs and addiction is doing to children, young people, whānau and communities. It was perceived by many to be an issue that was highly interrelated with poverty and hardship, both as a coping mechanism and a contributor to poverty and hardship. For example, the specific policy approach of reducing smoking through price increases was seen as ineffective and perpetuating inequity. Poverty and hardship causes stress, which drives people to smoke as a coping mechanism, which in turn increases poverty and hardship. People often talked about the need for alcohol, drug and addiction issues to be approached from a position of empathy, and for additional wraparound support rather than taking a punitive approach.

When I was 14 my friend invited me to his house, his mum showed us how to shoot meth. He never invited me again. That was his role model. You can't fix that. It will always happen like that. This country needs to show people that have severe addictions that they are loved, that they can be valued. A rat with no stimulus and the option of drugs will always choose drugs, a rat with something to do will do something. We all want to feel like we are a part of something, that people care about us. When we don't, anger takes control. We're only human.

Adult

Bullying, discrimination and racism#

Children and young people also said that bullying gets in the way of a good life. Bullying at school and online were the most common examples, but some children also spoke about bullying within their family or their homes. Bullying was an issue that was experienced in different ways for different individuals and groups, for example young people who identified as a part of the LGBTQI+ community mentioned online bullying more frequently than others. Tamariki and rangatahi Māori often linked bullying to racism. Some children and young people with disabilities spoke about being made to feel different because of their appearance. For some children and young people, bullying was so prevalent in their lives that it had started to become normalised.

It is very different today now because you can be bullied in your own bedroom on the phone. That is a big thing we should be careful of. There is cyber bullying.

Young person (pg.32*)

Some children and young people believed they aren't given the same opportunities as others, such as sports and activities. They felt that people judged them as less capable than others and, as a result, they were not offered equal opportunities. Young people talked about not being listened to at home, at school and by society. They said adults make assumptions about what they can or can't do and what they want. Some young people feel as though no one expects anything of them, or worse, everyone expects them to make bad choices and to fail.

Something I always have to deal with at school is the stigma. When people find out you're a foster kid they're like 'oh you're an orphan, whose house did you burn down?'

Young person (pg.33*)

Expectations - no role models, no inspirations, no goals.

Young person (pg.35*)

Adults talked a lot about the lack of representation of diverse cultures and backgrounds in positions of power and influence being key barriers to wellbeing. They told us that policy and services aren't always designed with the specific needs of different population groups in mind, for example LGBTQI+, people with disabilities, or people with English as a second language. Adults spoke about mainstream services and agencies lacking cultural competency at both a structural level and in the competencies of the people delivering the frontline services. They told us that Māori and Pacific Peoples in particular continue to be marginalised, that there is institutional racism at most levels of the system, and that there is a lack of regard for Māori and Pacific cultural intelligence.

Children and young people spoke about the impact that racism has on their lives. They gave examples of experiencing racism at school, in employment and in their community. Many children and young people talked about how racism is common in their everyday life. Racism was mentioned by a range of different children and young people, including those from refugee backgrounds, recent migrants, and Māori and Pacific Peoples.

At our school people find mocking Māori culture to be a joke. ‘Māoris go to prison', or ‘Māoris do drugs'.

Young person (pg.32*)

Māori service providers spoke of a sense of double standards, higher expectations, and inequitable funding for them compared to mainstream providers. This included having funding pulled and/or redirected to mainstream services if they didn't deliver radical change for Māori in short timeframes, despite the same mainstream services not working for Māori for decades. There was a strong call for these issues to be addressed.

Irrational fear of funders that Māori are incapable or can't be trusted to meet the needs of their own

Adult

Lack of Māori voice on key governance boards

Adult

Some young people and a number of adults talked about the impact of colonisation and a lack of respect for Te Tiriti o Waitangi. Tamariki and rangatahi Māori spoke about tokenism - one young person said that adults were happy to listen to rangatahi when those adults needed them to do a whaikōrero or pōwhiri, but would not listen otherwise. Tokenism was closely linked to racism for these young people. There was clear frustration from Māori that Te Tiriti o Waitangi continues to be ignored, or that its inclusion is tokenistic. Issues raised by participants at face-to-face engagements included lack of true partnership with Māori, not adhering to Te Tiriti principles, and a need for greater emphasis on Te Tiriti across the whole of government.

Bureaucracy, criteria and other access issues#

Children and young people talked about how ‘the system' can get in the way of a good life. The system usually meant Oranga Tamariki, Police, their school, the health system or Work and Income. Young people in care talked about how they didn't know what support they were eligible for and only learned about financial supports when other young people they knew got them. Some young people said they didn't feel that professionals such as their doctor, teacher or social worker understood them. They talked about their frustration with the services designed to support them and how they don't understand what professionals are telling them or what is required of them.

I've done all of these things, but nothing changes. Will all of Oranga Tamariki make a change? No little white lies.

Young person (pg.37*)

Adults also identified a range of barriers to children, young people and their families and whānau accessing the services they need. Cost of services, the indirect costs associated with accessing the services like transport or school uniforms, and long waiting lists were all identified as barriers to accessing appropriate services. Co-locating services where children spend their time, such as schools and marae, and increasing home visits and bringing the specialists to rural communities were suggested solutions to increase access.

There's a problem of accessibility: secondary students need a free school bus service, or there needs to be a new school built.

Adult

Health literacy, a general lack of knowledge about what supports were available and what they were eligible for, and difficulties navigating systems to gain access to services were also identified as significant barriers. Some of the families we engaged with told us how helpful the ‘navigators' provided through Whānau Ora had been at addressing some of these issues.

The navigators are really helpful. They help find support through means other than WINZ to help, like stationery and food parcels. They also help with the organisation stuff. The financial stuff [budgeting advice] is good and they are helping you get prioritised and organised WINZ

Adult

Adults also talked about experiences of different government agencies providing contradictory information or advice. There was a feeling that no one was willing to help and that agencies were referring families to each other in order to not have to be the one to “deal with the problem”.

There needs to be one government with one goal - no ‘wrong door' for us to enter.

Adult

A lack of capability or knowledge about how to navigate the requirements of “bureaucracy” was also identified as a barrier by support people working within the system. Service providers and NGOs in particular spoke about needing to hire someone specifically to manage the complicated administrative requirements of their contracts with government agencies.

We also heard that a lack of kaupapa Māori services is a barrier for many Māori, and a lack of cultural safety within mainstream services creates a barrier for Māori to participate. They told us that there is a need for Māori to create Māori services, as mainstream services are not working for Māori. There was also an expectation that all Māori, regardless of where they live, should have the option of access to Māori services.

Support that comes too late or only addresses a small part of the problem#

A common criticism from adults was that government agencies are not operating in a way that meets the needs of children, young people, and their whānau. High thresholds and restrictive eligibility criteria, were also identified as significant barriers. Adults told us they felt that the system does not appear to value the health and wellbeing of children, young people and their whānau. At the Ministry of Health workshops, participants identified that services are often focused on intervention during crisis, and on treating illness rather than prevention, particularly around mental health and behavioural issues. The “ambulance at the bottom of the cliff” was a common phrase that occurred throughout the engagement process.

Some adults spoke of falling in the gaps between agencies' criteria or services, and having to wait until problems got much worse before they could get the access they needed (e.g. a child, parent or family whose needs couldn't be meet by the mainstream services but whose needs weren't serious enough to qualify for the more intensive intervention services). Many of the adults who worked within the system, such as service providers or public servants, felt that the underlying funding system and organisational structures of government agencies was a significant barrier; it incentivises competition instead of collaboration between agencies.

Not receiving a quality education#

A lack of a quality education was a common theme identified as a major barrier by adults. Children and young people’s lack of education was seen as a barrier to their future wellbeing while parents’ lack of education was seen as a barrier to children and young people’s current wellbeing.

A number of general, and some specific, barriers within the education system were identified as getting in the way of children and young people receiving a quality education. These included funding related things like “stressed school system”, “under resourced schools”, and “ECE subsidy is not enough”, “not enough specialist teachers”, and “lack of resources”. Adults also identified some of the costs associated with education as barriers, for example uniforms, transport or student loans. There were barriers identified around teaching and the curriculum including outdated teaching methods, the breadth or depth of subjects being taught, and a lack of relevance to life skills.

Some people expressed the need for greater opportunities for whānau, as a whole, to continue education. There was also specific focus on the role that Early Childhood Education could play in enhancing child health and wellbeing.

Working with young people in isolation as issues and problems vs holistic and integrated support for them as a whole person

Adult

Education was also raised as an issue by children and young people. They mostly talked about education and learning as a thing that is important for their wellbeing, but many identified barriers within the education system. For some the education system is not serving them well.

We go to school having a ‘bad as' morning, we can't talk to them about it because they don't care and then you get kicked out of school.

Young person (pg.43*)

They talked about some of the costs associated with education, and how education needed to be funded so that all schools have equal resources and facilities. They talked about the stress that school can cause in their lives and specifically mentioned the NCEA system as not being helpful and being very stressful. They said that it needs to be okay to fail and that they want schools to be more accepting and respectful. ‘What' children and young people learn at school was frequently mentioned. They called for more life skills to be taught at school.

Not listening to children, families, and communities#

An overarching theme across the engagement was that government agencies do not listen or, if they do listen, they do not act on what they heard. There was a clear call for greater partnership with communities in co-design, decision-making and delivery of services, in addition to the need to listen to the voices of our tamariki, rangatahi, and whānau.

At the face-to-face engagements, many adults expressed frustration around previous government public consultation exercises, with many participants feeling they are having the same conversations over and over, or have not been listened to in the past.

There was also a degree of mistrust. Questions were raised as to whether this engagement process would be like many others that government agencies undertake, which have very few outcomes. People felt that they had heard these messages and promises of change before, but little change had eventuated. Pacific attendees in particular felt that Pacific values are often ignored or their importance diminished.

Could you please listen to us?

Adult

The 'one thing' children and young people need#

The 'Postcard to the Prime Minister' was a way for children, young people and adults to express their “big ideas” directly with the Prime Minister. The postcard was available online, and in hard copy at the face-to-face engagements. Additionally, both the adult and children's surveys also asked the question “What is the one thing you want to tell the Prime Minister about what children need to have good lives, now and in the future?”

A total of 2,007 adults and 3,761 children and young people answered this question. Around 400 of the responses from children and young people and all the responses from adults were analysed by the child wellbeing unit using a combination of computer automated text analysis techniques and a manual coding system. The remaining responses from children and young people were analysed by the What makes a good life? team. The key themes and findings from their analysis were similar, and have also incorporated in this section.

There was a huge range of responses - from single word answers such as “Love”, to responses that were over 500 words, covering many different topics and concepts. On average, each response was about 40 words and contained 4-5 different themes. For example:

They need hope that they will have a voice to be heard. They need love to be the most prominent part of their lives. They need understanding that uniqueness is a hallmark of who they are and should be embraced. They need fun, laughter, playfulness and space to be free to explore in nature.

Adult

To have the support they need to absolutely 100% without a doubt believe in their inherent value as human beings that they know are important, that they feel safe, that they feel like they belong in their communities and have support to be themselves in every aspect of their hauora.

Young person

The most common themes that were raised are discussed below. This is not an extensive list of all the issues talked about by children, adults, and young people.

...more support for their family and whānau#

‘Family and whānau' was one of the most common themes. The people who talked about family and whānau also talked a lot about support, education, money, homes, employment, and love. Having loving, supportive parents, family and whānau who spend quality time with their children was identified by children, young people and adults as one of the most important things that children and young people need to have good lives.

I think a good life is where your parents are there to support you and look after you and help you when you're in need. I feel safe around my Mum and Dad because they provide food for me, keep me healthy and safe, they take me to my after school activities if I need a lift. When I feel emotional, my mum is always there to listen to me when I'm upset. She understands what I'm going through. My dad makes me happy and tells bad dad jokes! They take me to school to educate me. I think family is the most important thing in our lives because they love and support and help you.

Young person

Children, young people and adults told the Prime Minister that we need to provide parents, families and whānau with more support. The wellbeing of the family is essential to the wellbeing of the child.

I have grown up with family being around me constantly and I think having family and good friends around children and young people do make a massive contribution to their journey. What is most important is the parents are just as supported as the children because what affects the child affects the family as a whole. Finding long-term solutions for our families will be great :)

Adult

Adults talked about how government, employers, and society more widely need to value and recognise the importance of parenting.

More focus on valuing the role of families as the centre of health and wellbeing for children. Through the use of the media (education) and providing employment opportunities, social community events all things that promote a parents sense of healthy connection with their children.

Adult

Children, young people and adults also spoke about providing more financial support, or better working conditions to enable parents to spend quality time and provide for their children.

The ability for our parents and care givers to take care of us with one job. That means that our parents have more time with us and are less tired. And we have more money.

Young person

Many adults talked about providing support through parenting programmes or educating parents about the emotional and practical skills and knowledge needed to raise children, particularly where parents had had poor role models themselves. This included specific suggestions about teaching things like nutrition, financial literacy, how to use positive reinforcement, set boundaries, and how to talk to kids in a way that supports growth and development.

Just because it was / is does not mean it needs to be! Educated whānau who don't just become parents but are made good parents through education and support. It is time to break the cycle and that means support at the beginning not at the end when it becomes expensive and often can be too late.

Adult

…investment in education#

Education was a very common theme that emerged, with references to education, schools, teachers and childcare. Education was widely talked about as a positive thing and an enabler for a better future. Adults talked about an investment in education as an investment in the future. Children and young people told us over and over again about the importance of learning. They know that education can help to set them up for success in life and help them achieve their aspirations.

I believe education is the key to unlocking anyone's potential. Investing in our schools to provide all children with greater opportunities and aspirations for themselves and their futures is key to children leading better lives now and in the future.

Adult

Having a better education so they can be something big when they grow up and have enough money to support their future family and future generation.

Young person

One of the most common things adults talked about in regards to education was the need for more funding and resourcing for education providers and making education cheaper. This included specific suggestions such as additional resourcing for low decile schools, and more support staff and learning support services. A lot of children and young people also told us that education needs to be cheaper, but they were more likely to focus on the costs that impacted on their parents, such as uniforms, supplies and lunches. There were recommendations from children, young people and adults to fund other non-educational services such as social workers, counsellors, and nurses through schools. Both adults and children suggested that schools should provide food, especially low decile schools.

Curriculum content and delivery also featured often, with children and adults alike suggesting that education should be more relevant to 'real life'. This included a greater focus on things like budgeting, self-care, social skills, and resilience to prepare them for life beyond the classroom, as well as ‘learning how to learn' to prepare them for a rapidly changing workforce. Te Reo Māori, New Zealand history, and sexuality education (including healthy relationships and consent) were specific subjects that children, young people and adults suggested the education system needs more of, or to do better in. Children and young people also wanted education to be more interesting, fun, and responsive to who they are as an individual. This included things like a request for more sports, longer lunchtimes, more arts, nicer teachers, more one-on-one support, and less exams or pressure to get high grades.

Children need great education and an education system that doesn't fail them, to give them the best possible chance at life. I think the education system is somewhat flawed. I think subjects like budgeting, understanding economics, money, loans, and other real life issues that we all face is vital and I wish that someone had of taught me this in high school.

Adult

I do love school and learning however being tested doesn't benefit all students. An exam or test is a fact vomit, it is about cramming in everything so you get a good grade. Everyone is unique and saying they are and not taking it into consideration that everyone learns differently is limiting our future. I know you will most likely not read this but if you do please learn about Finland's school system.

Young person

…people who support, love and accept them#

There were many comments about the importance of relationships that provide children and young people with a feeling of support, love and acceptance. Having a support network and the certainty that they have someone they can trust, rely on for support, and look up to was important to children and young people's wellbeing. There was a large cross-over with the ‘family and whānau' theme (discussed above) particularly when talking about younger children. Providing for children's and young people's emotional needs was also talked about in the context of peers, friends and other important adults in the children's lives such as teachers, older siblings, friends' parents and youth workers.

Aroha. Kei te aro auki to hā. Unconditional love. Whakaatu te aroha, whakaako i te aroha, mā te mana o te aroha ka puawai, ka tipu, ka ora te tamaiti. Show love, images of what love is on media, TV, marketing. More courses and gatherings of love, sharing and caring for others. Have more teachers with heart, true heart for the holistic-ness of the child and their whānau, not just their education.

Adult

To find a love for learning and to be supported by the people around them, both their whānau and government. To never have to live with a lack of love.

Young person (pg.53*)

Children, young people and adults talked about the importance of people being accepted for who they are, and being free to explore and develop their culture and identity. Adults were also more likely to talk specifically about children learning about their culture and heritage in regards to ethnicity, whereas children and young people talked about their identity more broadly - e.g. their sexuality, their friends, who they wanted to be or what they wanted to achieve. Discrimination and bullying also came up frequently.

I think we should all treat people the same even if they're different they should be respected.

Young person

A future that allows all children/youth from every ethnic background to have a promising future. As a young Muslim wearing a headscarf (hijab)… If we could find a way to change systematic discrimination, it would be beneficial towards all Muslim women. Thank you.

Young person (pg.52*)

For all children to feel they have the ability to be their best selves, without having their gender, ethnicity or socio-economic status define them.

Adult

An important part of being accepted, particularly for marginalised groups, was finding people who understand them and who they could relate to. Some young people explicitly noted how, in their experience, their parents or the other adults in their life (including professionals) weren't able to provide this support because they weren't able to relate to them, or those people lacked the emotional and social skills or experience to provide that support.

Someone who the youth can talk to. I am 14 years old and I'm not religious so I don't have many youth groups that I can go to. If you add the fact that I'm gay on top of that I pretty much have nowhere where I can meet new people (other than school). It would be great to see more support towards the LGBTQI+ community. I just want someone to understand what we go through.

Young person

To know that they are important/valued. They have a place in this world, they belong to groups of people that love and care for them, and whom they can identify with. For my community (deaf and hearing impaired children) this is not the norm. …other kids may struggle identifying with peers, but they can link/identify/see their future in family/whānau. Not so the case for our kids. Wellbeing results from knowing who you are and being connected with others like you.

Adult

…enough money for the basics, plus a little bit more#

Money, and the cost of things, came up in about a quarter of the postcards. Housing featured in about a quarter of the postcards, while food and other basics needs like clothing featured in about 15% of responses.

Many children and young people stressed that everyone should have their basic needs met. This was the most common theme identified in the messages to the Prime Minister in the What Makes a Good Life report. Food and having a good house were frequently mentioned, and some children worried about the homeless or other children who might not have the basics like shoes, lunch or somewhere safe and warm to sleep. Adults also talked about raising benefit levels, addressing poverty, and helping families who were struggling.

Money. There are lots of poor people. Don't say mean things like 'GET A JOB' and walk away. Do this, go to them and say 'Here have some more money it might help you.' Give some money to poor people. So I hope I have convinced you and the government to give poor people money.

Child

I think that it is incredibly important that families have enough money to be able to pay for basic things like food, clothing, bills and other necessities. When children go to school hungry or without enough warm clothing it impacts their ability to learn, communicate and participate in class. Without being able to do these basic things, it can impact their future career, and most importantly their wellbeing.

Young person

Children, young people and adults also spoke about how ‘just enough', is not enough. Many families are getting by, but still struggling financially. They have housing, but not quality housing; they can provide food, clothes and other essentials, but special occasions like birthdays and Christmas required saving all year, and they struggled to afford the ‘extras' like activities on the weekend or school trips.

Parents play the most important role in a child's development and future. At-risk families need the financial and developmental support to thrive, not just get by. The future depends on the start kids and families get now.

Adult

Relating to your question as to what makes a good life for children and young people in Aotearoa lots of things come to my mind, but one thing stands out to me because I relate to it. That is never worrying about running out of resources such as money. There have been times in my life where my family has been able to spend money on things that we don't need and not have to worry about having enough left over to pay for things that we do need, like food and rent. Those times were the best because there was no stress in our household and I could get cool things like new books, games, video games, and consoles without ever stressing out about being broke. So these are my reasons for why never having to worry about running out of money is one the most important aspects of a good life.

Young person

Is to spend more time with family and if they are poor they still get to do all the cool and fun activities that we get to do.

Child

…support for their mental and physical health#

Health featured commonly in responses from children, young people, and adults, with references to physical or mental health - people often talked about health as both. Spiritual health was mentioned in other parts of the engagement, but did not feature as strongly in the postcard responses.

To have good health. By having good health I mean to have good healthy food, clean water, do exercise and have a good medical treatment. Education is one of the most important things, we should all be allowed to have a good and free education. That way we can have opportunities in our lives and we can build a good life for ourselves. Mental and social health are really important and necessary in our day to day because young people want and need to know that they are loved and respected for who they are. Mental health is important because that way we make good decisions in our lives.

Young person

Children typically focused on physical health, e.g. eating healthy and getting exercise as important for their wellbeing. Children and young people also asked for better supports for those with a disability, and wanted children and young people to be able to go to the doctor or the dentist when they need to. Young people sent messages about providing more support for mental and sexual health. This included wanting better education about health issues, and a request for more counsellors. Adults talked about more affordable and accessible health services, particularly for rural communities and disadvantaged children. Hours outside school/work time, services such as dentists, nurses and counselling located within schools, and transport assistance were all suggestions to make services more accessible.

Access to facilities to keep me healthy (physically and mentally) and the ability to achieve my goals in life.

Young person

More public awareness around anonymous mental health counselling sites for teenagers. We have 1737 but often people don't know about it, or aren't sure if or how they can access it. Also, making sure it's completely anonymous, so parents or guardians can't trace it…

Adult

A lot of children, young people, and adults also talked about having access to healthy food and good homes (i.e. warm, dry, clean and healthy) as important to children and young people's health. More visible services, and educating parents about things like nutrition, breastfeeding, and the importance of maternal health and the first 1000 days of infant development, were also common themes for adults.

The first 1000 days from conception are the most important part of a child's development. Support through nutrition, housing and healthcare are a vital first step in early intervention.

Adult

I have more than one thing but I would like to enforce the cost of food issue. I care for children as an in-home educator and the lunch boxes of the lower income children are basically just sugar and junk food that leads to teeth issues and other issues as well e.g. concentration levels etc. I cannot afford it myself but every day I take that food out and supply them with a shared kai of fresh fruit and vegetables, I also grow certain vegetables with the children. It is not their fault they are not getting fed healthy food for healthy brain and body development and it is also not the parents' fault. It is the fact they cannot afford to buy or the parents are not educated properly

Adult

…to be heard and considered in decisions that impact on their lives#

Children and young people wrote that they wanted to be respected, listened to, taken seriously, and have their opinions taken into account when decisions were made that affected them. Adults also advocated strongly for children's voices and rights to be better recognised.

The ability to be heard and taken seriously on what they have to say

Young person

No family violence and no court. Kids have rights don't force kids to do stuff they don't want to.

Child

Children need to be recognised as active participants who can contribute to society and can contribute ideas and views on matters affecting them. Their inclusion in decision making on matters affecting them should be taken more seriously by our government

Adult

Children and young people need political representation to influence policy development, decision making and, most importantly, the allocation of resources. For example, we could give the parents of children under the age of 18 years old some additional voting rights on behalf of their children. Let's think outside the box!

Adult